Lieutenant Colonel Francis Skelly Tidy.

(1775-1835)

by Colin Jones FINS.

‘The Sword wears out the Scabbard’

In June 1840 a series of articles appeared in the United Service Journal

entitled ‘Recollections of anOld Soldier’ (1). A heart felt rendition of anecdotes by a daughter

illustrating the traits and character of

an anonymous veteran of 43 years service. The writer introduced her

father under the fictitious name of

‘Colonel Fred Franklin’, and expected all who had fought under him would

instantly recognise this fine

old soldier from the Peninsular and Waterloo battlefields. There was

indeed a cry from friends and

comrades in arms alike, many deducing that the authoress of the work to

be a Mrs Harriet Ward, whose

father was actually a certain Lieutenant Colonel Francis Skelly Tidy, a

Waterloo veteran who had

recently passed away. Additional stories and tales of this highly

respected man were sent and the

encouraging response prompted her to compile a more regular memoir of

her late father. Harriet could

not oblige the inquisitive readers immediately, as her husband, Captain

John Ward had been posted to

the east coast of South Africa. She accompanied him and began writing

about the conflicts she

witnessed for the United Service Journal and in particular the 7th

Frontier war (1846-1847). In turn, she

authored many works concerning her five years residence in Kafirland and

some even accredit her with

being the first female war correspondent. Eventually, on her return,

Harriet finally put pen to paper and

‘Recollections of an old soldier’ was published in book form in 1849.

The small hardback was not

meant to be a scholarly work, more in the caption of ‘reminiscences

through affectionate memory of

‘Old Frank’, her beloved father’. Thus the stories and anecdotes within

leaves the historian wanting of

some further military detail. Harriet’s brief glimpses of Tidy’s father

and siblings give enough clues to

research a simple family tree of his close relatives.

An impressive list of service awaits one that wishes to delve into

Lieutenant Colonel Francis Skelly Tidy’s military career, but space

within the journal inhibits a full appraisal, and the writer finds it

necessary to concentrate on more recent research, if solely to prolong

his memory for Mrs Ward. At the tender age of 16, ‘young Frank’s’

first experience of military life was a sow one, enlisting in the 43rd

Foot infantry in 1792, he was sent to the West Indies, being present at

the Siege of Fort Bourbon,

the campaigns on Martinque and Guadeloupe, was captured at Barville and

imprisoned for 15 months

aboard a hulk under the notorious regime of Victor Hughes

(2). The POW’s

were chained in pairs and

deprived of water for 36 hours, with their shackled companions passing;

‘none were by to set the living

free from the dead. Many hours he [Tidy] sat beside a dead friend, on

board that horrible ship, and in

that fearful climate’.

(3)

Eventually, Tidy was sent to France and released on parole returning to

England in 1795. In a short

while he was back in the West Indies as an ADC to Sir George Beckwith,

at that time Governor of

Bermuda. Returning to England once more, he met the exiled Louis XIII in

Edinburgh and struck a

lasting relationship. Louis used to tell Tidy he should be glad to see

him at some future and more

prosperous time at the French court, Tidy replied that,

‘when he

should have the honour of

congratulating His Majesty on his restoration to the throne, he should

not be in court trim; for he

hoped to march into Paris at the head of a regiment, and would not wait

to brush the dust from his

jacket, before he paid his visit of congratulation at the Tuilleries.

And Louis used to laugh and gave

him full permission to redeem his pledge in his own way, hoping he might

do so for both their sakes’.

(4)

Little did either know, at the time, that the pledge would come to

fruition in 1815.

In 1802 he joined the 1st Royals as a captain and was sent to Gibralter

to help the Duke of Kent’s forces

quell the internal disturbances. One story tells us of an angry mob

mistaking Tidy for the Duke himself,

and was shot at and nearly killed. Another, confirms a grateful

friendship when the Duke once told

Tidy’s wife that her husband had ‘Saved his life’. There can be

no doubt that these noble acquaintances

helped our hero rise through the ranks without purchase. Returning for a

third time to the West Indies,

as a Brigade- Major on Dominica, yet another notable event, which seldom

appears in history books; is

Tidy’s two week voyage with Admiral Lord Nelson on board HMS Victory

during the cat and mouse

search for the French fleet, around the Caribbean islands in May and

June of 1805. Nelson under the

assumption that the enemy fleet were bound for Trinidad and Tobago,

received on board his ships, a

reinforcement of 2000 men, Francis Tidy being one officer who went

aboard, unwittingly knowing the

vessel was to become, four months later, England’s most famous flag

ship. Having found that they had

been deceived by the enemy’s whereabouts who were again sailing across

the Atlantic, disembarked the

troops in Antigua, Lord Nelson shook hands with each officer as they

went over the side, Tidy looked

back and said:

‘My Lord, you have shaken hands with me as an officer

of the Royal regiment, once

more if you please, as Frank Tidy. Lord Nelson smiled, shook hands

again, and my father, sitting in the

boat, watched that pale and care-worn face to the last moment with

uplifted cap’. (5)

In September of 1807 he became Major of the 14th (Buckinghamshire)

regiment of Foot infantry and

served as Assistant Adjutant-General in the expedition to Spain under

Sir David Baird during the

harrowing retreat to Corunna. He served again on the staff during

Wellington’s passage of the Douro

and fought at the action at Grijo in May 1809. Returning to England it

was not long before he was

ordered away again. This time serving in the Walcheren expedition, ‘Old

Frank’ was lucky to come

away from that campaign unscathed; the prevalent malaria illness dubbed

the ‘Walcheren fever,’

claimed many thousands of lives for years following that dreadful

expedition to the Netherlands.

Receiving the Brevet of lieutenant-Colonel on the 4th June 1813, he

joined the 2nd battalion of the 14th in

Malta during the plague and in 1814 also served in Genoa. He was

recalled back to England to take

command of the newly raised 3rd battalion which was about to embark for

North America. However,

this war ended and another more pressing matter was on the horizon when

Napoleon escaped his exile

from the island of Elba and once again began hostilities. The 3/14th

were one of the few battalions near

to the south coast that could embark for Flanders at short notice.

Landing in Ostend in April 1815, the battalion by rights should never

have been present at Waterloo,

but for two fortunate turns of fate and Lt-Col Tidy’s stubborn

persistence. Being a battalion of young

raw recruits, they had been ordered to Antwerp for garrison duty, but

the enraged Tidy beckoned

permission from Lord Hill to join the main army for the oncoming

campaign. Whilst in Brussels, both

Lord Hill and the Duke of Wellington watched the battalion parade in the

square and the Duke

remarked;

'They are a very pretty little battalion – Tell them they

may join the grand division as they

wish'.

(6)

Their place in history still not assured, another turn of fate would

secure the 14th’s battle honour for all

time. Tidy’s battalion were attached to Colonel Mitchell’s 4th brigade,

in the 4th infantry division under

the command of Lt-General Hon. Sir Charles Colville, who had been

ordered to protect the extreme

right flank of the allied army situated around the town of Hal. In turn,

Colville’s two other brigades

were too far away to take any part in the forthcoming battle, but by the

retrograde movement of the

second Corps marching from Nivelles, Mitchell’s brigade was swept up by

Lord Hill, the Corps

commander, on his way through to the field of Mont Saint Jean, and by

the evening of the 17th June,

Tidy’s battalion found itself in a position to the north-west of the

Chateau de Goumont. It is for this

reason that the 4th brigade temporarily became attached to Sir Henry

Clinton’s 2nd Infantry Division. On

the day of the great battle, Mitchell’s brigade, consisting of the

1/23rd foot,1/51st light infantry and the

3/14th who were positioned across the Nivelles road behind the Chateau

on the far right of

Wellington’s battle line.

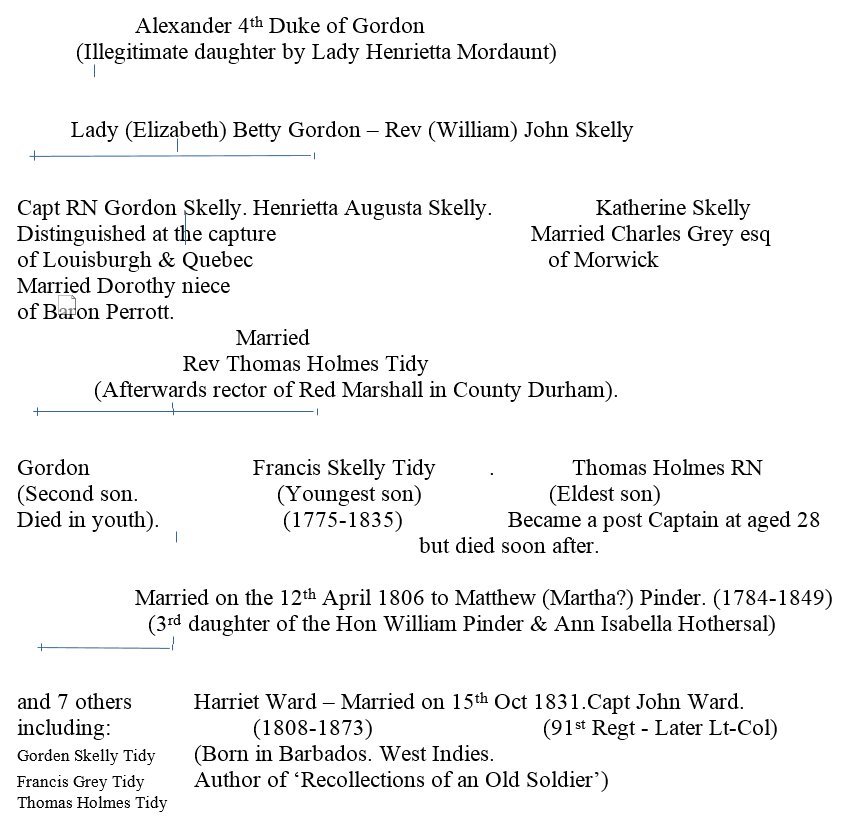

‘Old Frank’ already inadvertently had a tenuous connection to the battle

through his great grandfather’s

lineage, Alexander the 4th Duke of Gordon. The Duke’s eldest child, by

his first wife, was Lady

Charlotte who eventually married Charles Lennox the 4th Duke of

Richmond, and she was of course the

hostess to the most famous ball in history on the evening of the 15th

June 1815.

Although Tidy’s battalion played little part in the principal actions of

the day, being on the reverse side

of the plateau, they still suffered quite significantly from cannon

fire.

'The whole day we were exposed

to the fire of several batteries of artillery, and particularly two

pieces brought to bear upon us. I can

well remember the interest I took in those pieces-an interest heightened

by the consciousness that I

formed part of that living target against which their practice was

pointed'. (7)

The commander ordered ‘His Boys’ to lie down, and being in a

Square formation, the recumbent

position had the men Packed together like herrings in a barrel.

It was during this moment when Skelly

Tidy lost his favourite mare. Ensign Keppell continues the story;

'Not finding a vacant spot, I seated

myself on a drum. Behind me was the Colonel’s charger, which, with his

head pressed against mine,

was mumbling my epaulette; while I patted his cheek. Suddenly my drum

capsized and I was thrown

prostrate, with the feeling of a blow on the right cheek. I put my hand

to my head, thinking half my face

was shot away, but the skin was not even abraded. A piece of shell had

struck the horse on the nose

exactly between my hand and my head, and killed him instantly. The blow

I received was from the

embossed crown on the horse’s bit'. (8)

Mrs Ward’s account of her father’s loss differs in one small detail to

that of Ensign Keppell, she

remarks;

‘The animal plunging into her agony, threw the square into

great confusion, and her misery

was speedily put an end to by the soldiers bayonets’. (9)

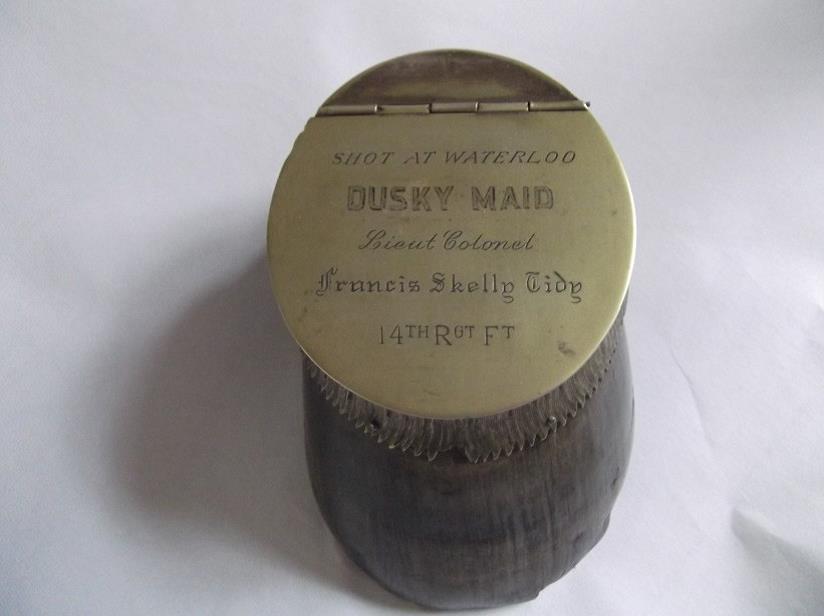

Francis Skelly Tidy’s mare ‘Dusky Maid’, killed at Waterloo. The

horseshoe was made into

an inkwell and was purchased by the author upon the sale of Derek

Saunders Waterloo

Museum, Broadstairs, Kent, by Wallis & Wallis in 1999. The engraved

letters are of mid-19th

century, suggesting the hoof was converted latter by a family member,

perhaps even by

Harriet herself.

The persistance of the barrage is again confirmed in a letter written on

the 23rd by Lieutenant Henry

Boldero, 14th Foot, to his mother;

'What a glorious battle! And what a

lucky woman you are to have had

two sons in it and neither of them touched.

(10)

Lonsdale

had three horses shot under him in two days

and yet escaped – and I lay under the heaviest cannonade that ever was

brought to bear in a Battle for

seven hours – and yet had the same good fortune – you may depend upon it

we are reserved for some

more ignoble exit'. (11)

The steadfastness of the battalion was again put to the test around 4

o’clock in the afternoon when the

French Marshal Ney launched his magnificent, 4000 strong cavalry charge,

along the main Allied

ridge. As Wellington’s entire line hurried into square formations to

receive the onslaught, a menacing

black mass of Heavy Cuirassiers emerged from the crest, stalling for a

moment to settle on which

battalion they would devote their attention. The alarm on the new

recruits faces were widely apparent,

Tidy had to steady his ‘Boys’ on more than one occasion. History

tells us that fourteen officers and

three hundred men of the 14th were under the age of twenty one. The

commander would have to draw

from his vast experience of nearly 24 years service to contain the

apprehensions of his “Raw

Johnny’s”.

Harriet Ward quotes her father’s words;

'Now, my young tinkers, stand

firm! While you

remain in your present position, old Harry himself can’t touch you; but

if one of you give way, he will

have every mother’s son of you, as sure as you are born'.

(12)

According to Cannon’s history of the 14th the Cuirassiers were

intimidated by the steady and

determined bearing of the battalion and instead chose to attack a

Brunswick square to the left.

Harriet continues;

‘after several attempts to break the square, they

sounded the retreat, and retired in

the utmost confusion. The attacked regiment waited only until the enemy

was entirely clear of the 14th

when they opened upon them with a most murderous fire, while at the same

moment several guns on

the side of my father’s corps, played upon them. For a minute or two,

the smoke was so dense, that it

was impossible to see a yard in advance; but when it cleared away, a

scene of the greatest disorder

presented itself. Numbers lay strewed about in all directions – dead,

dying, and wounded, - Horses

running here and there without their riders, and the riders encumbered

with their heavy armour,

scampered away as best they could, without their horses’.(13)

Despite having no physical bayonet contact with the enemy, a stationary

target can sometimes be richpickings; from a field strength of some 649, casualties of the 14th on

the day were 36 in total being, 3

officers wounded, with 7 killed and 26 wounded from the rank and file. A

further five men would later

die from their Waterloo wounds.

Tidy’s near neighbours ie: the 23rd and 51st lost 104 and 42

respectively, all these mostly from artillery

fire.

(14)

The young battalion were affectionately known as the ‘Johnny Raws’

following the battle, as many of

the men had gathered up some of the spoils of the vanquished which lay

around the fields in

abundance. Cuirassier helmets, Hussar pelisses, Grenadier caps and

bearskins were proudly worn as

they marched away from the battle site the following day. The Peninsular

veterans laughed and shook

their heads in despair; these old hands would never have imposed such

added weight and burden to

their kit.

With the 4th brigade being temporarily detached, General Colville’s

remaining part of the division

stationed at Hal, had apparently heard nothing of the victory despite

being only 12 miles away. At least

that was the case until his A.Q.M.G. Lt – Col John Woodford, who had

galloped off in the early hours

of the 19th had delivered to him the grim news of the substantial loss

of life. Woodford had been sent by

his commander to Mont Saint Jean to obtain further instructions from

Wellington. Arriving early on the

morning of the 18th the Duke told him that the battle was imminent, and

said that it was too late for the

division at Hal to move up, but added,

“Now that you are here, keep

with me”

(15)

Compared to some of Wellington’s Regiments, Mitchell’s brigade had

suffered relatively little during

the battle, and probably for this reason, as the Allied Army followed

Napoleon’s retreat through

northern France, they were selected to attack the fortified town of

Cambray. The brigade having

rejoined General Colville’s infantry Division, met with pockets of

resistance as they marched quickly

onto the capital city. The Division halted at Cambray where the Governor

of the place refused to

surrender to any terms and had locked himself up in the citadel with a

sizeable force. The town

however, first had to be taken by escalade, and Wellington gave Colville

two additional brigades of

artillery for this purpose. At 8’Oclock on the evening of the 24th June,

under cover of eighteen pieces of

cannon, the 3/14th battalion debouched from their cover and made a rush

for the horn-work of the Paris gate. Tidy describes the attack in a letter written two weeks after the

event;

Two of the brigades were

ordered to attack it one side, whilst ours, the 4th the only one engaged

on the 18th were to make a feint

on the other, which we did accordingly; but having got close to the wall

with a few hay stack ladders

tied together we resolved to our luck in a quick attack: my position

happened to be on a bridge with a

great part of the 51st and all of my own who were getting two at a time

over the top of the gate; which

being tedious we knock’d at the gate and an inhabitant or two actually

let down the bridge and we

walked in in sub-divisions. We marched onto the Grand Square and formed

up in the most regular

order of columns of battalions. Negotiations were set going for the

surrender of the citadel a place of

great strength and suspense agreed on 5 o’clock the day after tomorrow

in the morning, but the fellow

gave in and we started for Paris, encamping on the 1st july before Monte

Matre. The convention of

suspension agreed upon, you will see more of than we do, in fact we know

nothing of what is going on.

I hope Bull is satisfied.

(16)

Despite Tidy’s modest description. Six men were wounded in the attack of

which two later died of their

wounds. Colville states that of the 3 brigades engaged, he had one

officer killed and 40 rank and file

killed or wounded. 20 of the enemy were taken prisoner at the Paris

Horn-work and another 130

altogether in the town.

(17)

Following a short stay with the Army of occupation in France, the 3rd

battalion was sent home and

disbanded at Deal on 17th February 1816. The short life of the battalion

had lasted barely two years.

Colonel Tidy was nominated a Companion of the Bath and immediately

embarked in command of the

2/ 14th for the Ionian Islands. Returning to England for a short leave,

he sat for the English Portrait

painter, James Ramsey (1786-1854). The portrait is currently held at the

York Army Museum.

Colonel Francis Skelly Tidy Wearing his Companion of the Bath

and Waterloo Medal.

Tidy then took command of the 1st Battalion, serving in Bengal and with

whom he stayed as Deputy

Adjutant General under Lt-Col Sir Archibald Campbell, from 1819 through

to 1826; and a further two

years as an unconfirmed Lieutenant - Colonel of the 59th Regiment. These

nine years of war in India

fighting the Burmese rebels and battling against the oppressive climate,

took many of the soldiers lives.

When the rainy season set in, so did the Cholera and Malaria. Camping

beds made from blankets and

propped up with sticks in marshlands above stagnant water; Colonel Tidy

was one who suffered

severely, only putting his survival down to a single fastidious routine:

‘We have a good deal of fever, in consequence of the constant dampness

of the air. I had it slightly, and

have kept myself well by having my Dobee (washerman),with his iron at my

bedside at daylight every

morning, to iron my clothes before putting them on- they are never dry

otherwise’.

Before the termination of the war, the privations began to tell on his

constitution and Tidy’s health

never did fully recover from the ravages of the extreme heat and

water-borne maladies of the East

Indies. Doctors advised him that it would not be prudent to remain in

residence in India and was sent

home in 1828. Tidy now, as a commissioned Lieutenant – Colonel, took

command of the 44th Regiment

as Inspecting Field – Officer and was stationed in Glasgow until 1833.

Even though the years of travel

were beginning to tell on his physical appearance and general well

being, he still yearned for active

service and to be in full command of a Regiment. A near friend wished to

persuade him against reentering

any more active scenes of life and even perhaps retire. Tidy who was now

58 years old replied:

‘you do not take into account what a fine thing it is to have it in your

power to make eight hundred

people happy.’

Tidy’s Daughter Harriet, knew that truly, ‘the sword was wearing out

the scabbard!’ On the 1st March,

1833, he exchanged from his position at Glasgow to the Lieutenant –

Colonelcy of the 24th Regiment,

who were then posted abroad. As soon as Harriet saw him gazetted in the

newspapers her heart sank:

‘I

looked upon his doom as sealed,- for his destination was Canada: a

fearful climate to encounter after

the sultry heat of India, and with a shattered constitution’.

Furthermore, once Tidy had disembarked on the shores of his final

destination in the spring of 1833, he

was greeted by an official letter stating that all his savings of nine

years service in India had been lost.

The banking house of Messrs. Ferguson and Co. in Calcutta, had gone

bankrupt! A trifling dividend

was to be paid to its creditors before the firm folded, and there was to

be no appeal. Such a crisis at

Tidy’s time of life was distressing to say the least – his entire

fortune had vanished. Needless to say, the

remaining nineteen months of his life were spent undertaking his

military duties during the rebellion

suppression at this time, and once more gaining the admiration of his

men. Lieutenant Colonel Francis

Skelly Tidy passed from this world on the 9th October 1835 aged 60, and

was buried at the Kingston

garrison in Canada. Harriet was convinced that the many years of disease

ridden locations were the sole

cause of his early demise. A fitting tribute was later affected by one

singular occurrence; Sergeant major

Maltby, being quartered in Canada, requested in his last moments, that

he might be laid in a

grave close to that of his old commanding officer. Having three rounds

fired over the grave, the volleys

served a dual-purpose, having been one of Tidy’s earnest wish; the

firing party and the deceased, were

all men of the 14th Regiment.

Such was the career and life of a dedicated regimental officer of the

old school. Serving his country

with distinction during some of the most critical periods in history,

and a veteran of merit who through devotion and loyalty to his country, raised himself beyond the

limitations of most.

Perhaps our hero should have followed in the footsteps of one of his

‘Waterloo Boys’, Mr Matthew

John Marsh, one of the ‘Johnny Raws’ in the 14th Foot Regiment at

Waterloo, who had also later served

in the East Indies. With the prize money obtained in the war and a

legacy he received at the time, he

bought his discharge and returned to fairer shores. On his way back to

England from India he passed

through Paris and was present at the second burial of Napoleon, giving a

profound conclusion to his

military career. Matthew lived to the ripe old age of ninety-two.

(18)

References:

1)

United Service Journal and Naval and Military Magazine. Vol 33, part

2, June to Aug 1840. Pages

205-214, 353-359 & 474-481.

2)

Victor Hughes appointed governer of Guadeloupe in 1794. Took

horrifying revenge on any who

supported the British cause.

3)

USJ. Page 207.

4)

Recollections of An Old Soldier: A biographical sketch of the Late

Colonel Tidy, C.B. By Mrs Ward.

London Richard Bentley 1849. Page 40.

5)

Recollections. Page 57.

6)

Probably the best recent study of the 3/14th is written by Steve

Brown, for the Napoleon series web

site, entitled ‘A very pretty little battalion’.

7)

Keppell, George Thomas. Fifty Years of my Life. New York: Henry Holt

& Company1877. Page

102.

8)

Fifty Years of my Life. Page 103.

9)

Recollections. Page 106.

10)

Lt. Lonsdale Boldero. 1st Regt Foot Guards.

11)

Brett-James, Antony. The Hundred Days. London Macmillan & Co. 1964.

Page 205.

12)

Recollections. Page 104.

13)

Recollections. Page 105.

14)

Bowden, Scott. Armies at Waterloo. Empire Press. 1983.

15)

A Brief memoir of Major-Gen. Sir John Geo. Woodford, A paper read to the

Keswick literary and

scientific society on March 29th 1880. by J. Fisher Crosthwaite, F.S.A.

London 1883. Page 23 & 29. Sir

John Woodford was the brother of Sir Alexander Woodford.

16)

Letter from Lt Col Francis Skelly Tidy, held by the Yorkshire

regiment, at the York Army Museum.

Headed: The camp in the Bois de Bologne, 8th July 1815. A copy of which

was kindly lent to me by

Paul F. Brunyee, Honorary Editor of The Waterloo Association.

17)

A good description of the affairs at Cambray can be found in: The

Battle of Waterloo, containing a series of accounts published by

authority, British & Foreign with circumstantial details relative to the

battle. By a near observer. 1816. Also Colville’s letters in, The

Portrait of a General by John Colville.

Michael Russell publishing. 1980.

18)

Obituary of Mr Matthew John Marsh. Guardian. June 9, 1886.

Inscription

To

The Memory

OF

COLONEL F.S. TIDY C.B.

Who died whilst in Command of

His Majesty’s 24th Regiment of Foot

in this Garison

on the 9th October 1835

at the Age of

60 Years

This Tomb was Erected by

The Officers Non Commissioned Officer Brigade

of the above Corp

a Tribute

of

RESPECT AND ESTEEM

for

COLONEL AND OFFICER

who served his

KING AND COUNTRY

___hfully

for a period of

43 years

The Portsmouth Napoleonic Society

'Over The Hills and Far Away'